Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans: Deadly fungal threat to salamanders

31 July 2015Tiffany Yap & Michelle Koo

Updated October 2018

Content:

- Magnitude of Threat

- National Actions

- In the News

- Conservation Action

- What you can do

- Salamander Fungus video featuring David Blackburn

- References

Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal), a fungal pathogen that causes chytridiomycosis in salamanders, rocked the amphibian conservation world by causing mass die-offs in wild European fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra) in the Netherlands; it has since spread to Belgium and Germany. First described in September 2013 (Martel et al 2013), Bsal is much like its relative Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd). Bsal has aquatic zoospores that infect the skin of the animals, which leads to skin lesions, anorexia, apathy, ataxia and death. It is hypothesized that Bsal originated in Asia and arrived in the Netherlands via the international pet trade (Martel et al 2014). Based on field surveys and lab experiments, Martel et al. (2014) hypothesize that there are at least three reservoir hosts: Cynops cyanurus (from China), Cynops pyrrhogaster (from Japan), and Paramesotriton deloustali (from Vietnam). In their study, Martel et al. (2014) assessed 24 species of salamanders from 5 families and found that species from the families Salamandridae and Plethodontidae, particularly newts (family Salamandridae), were found to be the most susceptible to the disease.

|

|

|

| Cynops cyanurus, photo by Todd Pierson | Cynops pyrrhogaster, photo by Mark Aartse-Tuyn | Paramesotriton deloustali, photo by Henk Wallays |

Bsal has not been documented in the wild outside of Asia, the Netherlands, Belgium, or Germany; however, few surveys have been conducted to determine its global extent since its discovery (Bales et al. 2015; Muletz et al. 2014). What we do know is that of the 24 salamander species that have been tested, Bsal is lethal to at least 12, including Taricha granulosa and Notophthalmus viridescens (family Salamandridae) (Martel et al 2014). Both species have expansive ranges within salamander biodiversity hotspots, can occur locally in high densities, and play important ecosystem functions.

|

|

| Taricha granulosa, photo by Aaron Schusteff | Notophthalmus viridescens, photo by Henk Wallays |

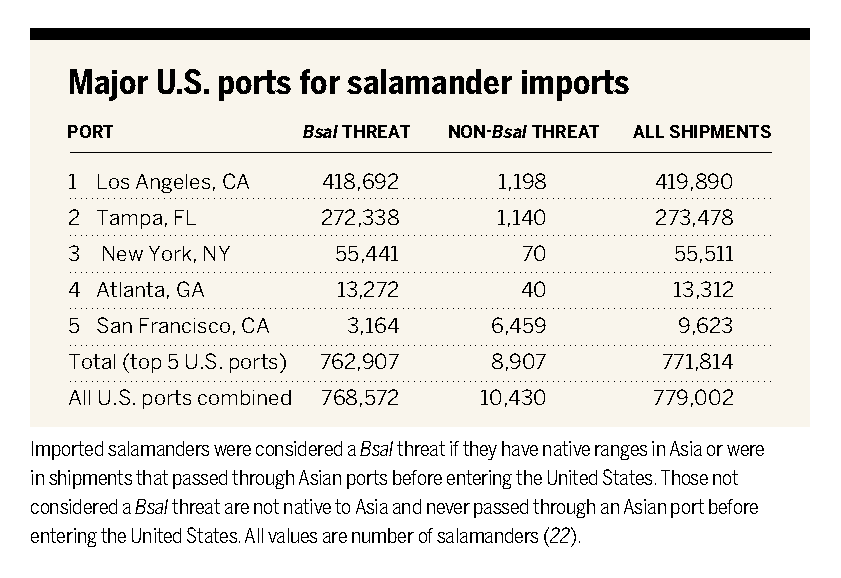

In the last 5 years (2010-2014), 99% of US salamander imports originated or passed through Asia, and 91% were from the genera Cynops or Paramesotriton (Yap et al. 2015), which include the proposed reservoir species (Martel et al. 2014).

Yap et al. (2015) predicted areas of salamander vulnerability to Bsal in North America, the world’s salamander biodiversity hotspot with almost 50% of the world’s salamander species. They identified the southeastern US (the southern extent of the Appalachian Mountains and neighboring southeast region), the western US (the Pacific Northwest and the Sierra Nevada) and the central highlands of Mexico (portions of the Sierra Madre Oriental and the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt) as high vulnerability zones based on potential Bsal habitat suitability, species richness, species endemism, and potential ports of entry.

|

|

| Bsal Vulnerability Model for North America (Yap et al. 2015) | From Yap et al. 2015 |

Based on what we've learned from more than a decade of Bd outbreaks and research (Wake and Vredenburg 2008; Stuart et al. 2004; Skerratt et al. 2007), the consequences of Bsal invading the wild populations of North America will be severe and irreversible. Given the vulnerability model, the risk of Bsal invasion is high. Several conservation groups and scientists have submitted letters to the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) urging them to implement an emergency moratorium on all live salamander imports into the US, and on May 14, 2015 the Center for Biological Diversity and Save the Frogs! submitted a formal petition for a moratorium.

In January 2016, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, taking into consideration many concerned scientists speaking up, issued an interim ruling that bans the importation of over 200 species of salamanders, targetting the species most likely to carry Bsal. Their news release is accompanied with a list of the deemed injurious species that are banned and a "Q & A" fact sheet, all available on their site.

Read the full USFWS Interim Ruling (2016-000452): "Injurious Wildlife Species; Listing Salamanders Due to Risk of Salamander Chytrid Fungus" (PDF download).Meanwhile, researchers and organizations are working to address this wildlife emerging infectious disease crisis. The Singapore Zoo, the Animal Welfare Institute, Defenders of Wildlife, and the Amphibian Survival Alliance held an International Amphibian Trade Workshop in March 2015 to assess the impacts of global trade on amphibians worldwide. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative (ARMI) and the Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (PARC) National Disease Task Team are working to implement surveillance and monitoring programs to detect Bsal and other emerging infectious diseases in the US.

In the News

What AmphibiaWeb is doing

In early 2015, AmphibiaWeb started organizing an amphibian disease portal that will provide a centralized database for researchers to archive and access disease data with the aim of helping facilitate and coordinate monitoring efforts. By summer, we started a collaboration with the USDA Forest Service to make it happen. We launched community discussions about the portal at the SSAR Annual Conference in Lawrence, KS, USA and now have a beta version at Amphibian Disease.

More Resources:

Southeastern Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, Disease, Pathogens and Parasites Task Team (PDF)

What you can do

Check back on AmphibiaWeb for the latest news and requests for feedback from users and researchers. We post Disease Portal updates on our project blog, and you can always contact AmphibiaWeb directly.

Precautions from the husbandry best practices are important to follow:

- Avoid buying Asian salamanders until better precautions are in place.

- Never release pet salamanders into the wild, including those that you collected yourself and kept in captivity for at least 30 days.

- Treat waste water from tanks with bleach before pouring down the drain.

- Get involved with your local herpetological society and find out how to help educate the public.

Science Today: Saving Salamanders from AmphibiaWeb's David Blackburn

Bales, E. K., Hyman, O. J., Loudon, A. H., Harris, R. N., Lipps, G., Chapman, E., Roblee, K., Kleopfer, J.D., and Terrell, K. A. (2015). Pathogenic Chytrid Fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, but Not B. salamandrivorans, Detected on Eastern Hellbenders. PLOS ONE, 10(2), e0116405.

Martel, A., M. Blooi, C. Adriaensen, P. Van Rooij, W. Beukema, M. C. Fisher, R. A. Farrer, B. R. Schmidt, U. Tobler, K. Goka, K. R. Lips, C. Muletz, K. R. Zamudio, J. Bosch, S. Lötters, E. Wombwell, T. W. J. Garner, A. A. Cunningham, A. Spitzen-van der Sluijs, S. Salvidio, R. Ducatelle, K. Nishikawa, T. T. Nguyen, J. E. Kolby, I. Van Bocxlaer, F. Bossuyt, and F. Pasmans. (2014). Recent introduction of a chytrid fungus endangers Western Palearctic salamanders. Science, 346(6209), 630–631.

Martel, A., Ppitzen-van der Slulis, A., Blooi, M., Bert, W., Ducatelle, R., Fisher, M.C., Woeltjes, A., Bosman, W., Chiers, K., Bossuyt, F., and Pasmans, F. (2013). Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. causes chytridiomicosis in amphibians. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(38), 15325–15329.

Muletz, C., Caruso, N. M., Fleischer, R. C., McDiarmid, R. W., and Lips, K. R. (2014). Unexpected rarity of the pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Appalachian Plethodon salamanders: 1957-2011. PLoS ONE, 9(8), 1–7.

Skerratt, L. F., Berger, L., Speare, R., Cashins, S., McDonald, K. R., Phillott, A. D., Hines, H. B., and Kenyon, N. 2007. Spread of chytridiomycosis has caused the rapid global decline and extinction of frogs. EcoHealth 4: 125-134.

Stuart, S., Chanson, J. S., Cox, N. A., Young, B. E., Rodrigues, A. S. L., Fishman, D. L. and Waller, R. W. (2004) Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306: 1783-1786.

Wake DB, and Vredenburg VT (2008) Are we in the midst of the sixth mass extinction? A view from the world amphibians. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105:11466-11473.

Yap, T.A., Koo, M.S., Ambrose, R.F., Wake, D.B., Vredenburg, V.T. (2015) Averting a North American biodiversity crisis. Science 349(6347):481-482 doi:10.1126/science.aab1052 Paywall getting in the way of access? Download here for free access (Pub #51).