|

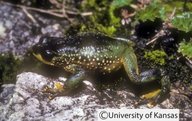

Atelopus peruensis Gray & Cannatella, 1985

Peru Stubfoot Toad | family: Bufonidae genus: Atelopus |

© 2010 Division of Herpetology, University of Kansas (1 of 5) |

|

|

|

Description Atelopus peruensis is a harlequin toad from northern Peru. The snout-vent length ranges from 32.80 - 38.50 mm in males and 38.40 - 45.20 mm in females. The head’s width and length are about equal and it is not as wide as the body. The snout somewhat tapers off in the dorsal and lateral perspective, and it juts out past the lower jaw. The nostrils point in the lateral direction and are located at the level of the highest point of the lower jaw. The canthus rostralis is prominent, pointed, and straight from the nostril to the tip of the snout. The loreal region curves inward. The lips are not flared. The interorbital region is level. The top of the snout curved inward slightly. The postorbital crest is prominent. Atelopus peruensis lacks a tympanum. The only tubercles on the head exist on the region posterior to the corner of the jaw and below the post-orbital crest. There is no co-ossification between the skin on the head and the skull. Atelopus peruensis lacks vocal slits but has the ostia pharyngea (Gray and Cannatella 1985). The skin on the dorsum is slightly areolate and has more tubercles in the lateral direction. The tubercles decrease in the dorsolateral and postorbital areas. There are also tubercles on the upper arm that continue to the pectoral region at the point of attachment of the arm. The skin of the limbs’ dorsal surfaces is somewhat tubercular. The palms and soles are fleshy and have creases. The skin of the underside is granular and has prominent creases. the skin on the anal and pectoral regions is somewhat more granular (Gray and Cannatella 1985). The forearm has some low tubercles down the ulnar edge. The thenar and palmar tubercles are defined and fairly flat. The subarticular tubercles are oval-shaped and not clearly defined. The digital pads are rounded and not clearly defined. The fingers have a bit of webbing, but do not have fringes. There is a horny nuptial outgrowth on the thumbs. The thigh and shank do not have any tubercles or folds. The tarsus has some low tubercles on the outward-facing edge. The inner metatarsal tubercles are about twice the diameter of the outer metatarsal tubercles and they are both defined. The toes’ digital pads of the toes are more defined than the fingers’ pads. The subarticular tubercles are not strong. The toes are webbed three-quarters of the way with fleshy webbing. The webbing continues to all the digital pads on the toes besides the fourth toe, where there is a lateral fringe down the distal side of the toe (Gray and Cannatella 1985). Tadpoles in the Gosner stages 25 - 32 have a body length that ranges from 5.0 - 8.3 mm and a total length that ranges from 9.2 - 17.0 mm. The diameter of the eyes is roughly half of the distance between the eyes. There is a small longitudinal depression along both sides of the vertebral column. The nostril is a bit closer to the eye than the snout tip. There is strong caudal musculature. The dorsal fin is somewhat raised at midlength. The ventral fin is a bit curved (Gray and Cannatella 1985). Atelopus peruensis adults can be differentiated from A. spumarius because the former lacks a columella and the latter has a concealed tympanic annulus. Atelopus peruensis differs from A. willimani, A. tricolor, A. rugulosus, and A. eryth because A. peruensis is larger and not as slender, does not have dorsolateral stripes, nor does it have bright red colors on its feet. Atelopus peruensis can be distinguished from A. seminiferus by the latter’s longer body and limbs, venter that is a brown-orange color, small yellow tubercles on its flanks and feet, and more webbing on the feet. Atelopus peruensis can be differentiated from A. arthuri by the latter’s vermiculate dorsal pattern, red underside, slimmer limbs, and its lack of pale yellow tubercles on the flanks. Atelopus peruensis is distinguished from A. nepiozomus by the latter’s smaller size and slender body, pointed head, snout that is acuminate in the lateral view, feet that are less webbed, and a brown anal patch. Atelopus peruensis is distinct from A. pachydermus because A. pachydermus has dorsal blotches that are bright yellow. Atelopus peruensis is different from A. halihelos because A. halihelos is smaller and has slimmer limbs, a snout that is more acuminate, has a less defined thumb, and has glandular swellings throughout its body. Atelopus peruensis can be differentiated from A. bomolochos by A. bomolochos’ larger size and its small spicules on its flanks in replacement of the larger tubercles that we see on A. peruensis. Atelopus peruensis is distinguished from A. ignescens by the latter’s lack of pale yellow tubercles on its flanks and its consistently dark dorsal and palmar and plantar surfaces. Atelopus peruensis is distinct from A. exiguus by the latter’s smaller size and yellow-green dorsum (Gray and Cannatella 1985). Atelopus peruensis is different from A. oxapampae by the former’s stronger, toad-like body, and its green and black dorsum that lacks stripes (Lehr et al. 2008). Atelopus peruensis can be distinguished from A. pyrodactylus by the former’s stronger body, less noticeable vertebral neural processes, lack of warts on the gular region, the lack of coni on the dorsolateral region and flanks, warts that are white or yellow on the black flanks, and a venter that is entirely pale orange to yellow. They can also be differentiated by the latter’s tan dorsal markings (Venegas et al. 2005). In preservative, the dorsum of adults is mainly black-brown and transitions to a blue-gray in the posterior and lateral areas. The limbs’ dorsal surfaces have similar coloration but the inner digits of the hands and feet transition to a cream color. The other regions that are cream colored include the ventral surfaces, certain parts of the groin, upper lips, region below eyes and posterior to the nostril, the ventral side of the flanks, and the digital pads’ dorsal surfaces. There are some black regions on the dorsum from the postorbital region to the groin. There are pale yellow tubercles on the flanks and postorbital regions. The horny nuptial outgrowth on the thumbs are brown (Gray and Cannatella 1985). In life for adults, the dorsum ranges from bright to dull green and black. The flanks are black and have yellow tubercles but some have flanks that are entirely dull green. The dorsal surfaces of limbs have similar coloration to the dorsum. The ventral surfaces range from bright yellow to pale orange. It has dark brown irises (Gray and Cannatella 1985). For larvae, in life, they are black with pale gold marks on dorsum and caudal musculature. The body has dark brown coloration and is mottled with gray. The suctorial disc’s flange is pigmented in the lateral direction and the amount of pigment decreases in the posteromedial direction. There are very small flecks on the body and tail, and they are the most concentrated on the anterior half of the ventral fin (Gray and Cannatella 1985). Individuals vary in coloration. Dorsal melanism ranges from substantial to hardly present, spanning from dispersed darkening on top of the green ground color, to mottled mixture of black and green, to primarily black. There may be distinct dark markings on the dorsum or limbs. Those with mottled coloration typically have darker heads. The broad black stripe that starts at the temporal region and continues through the axilla to the inguinal region in some individuals may be smaller or interrupted in others, but it is always present. The anal region typically has patches of dark pigment. Some may have the dark dorsal coloration reach the palms and soles’ periphery and continue to the digits’ ventral surfaces. The venter and digit tips of the palmar and plantar tubercles are entirely pale. There is also some sexual dimorphism. The snout-vent length for males is about 80% of the snout-vent length of females. Overall, males are generally smaller than females. Females have more numerous and larger sharp, thickened spinae of horny material at the tips of their tubercles, and these spinae mainly exist in small aggregates. Males’ spinae are less developed and their tubercles may lack the spinae (Gray and Cannatella 1985). Distribution and Habitat Country distribution from AmphibiaWeb's database: Peru

Atelopus peruensis lives in the high elevations of the puna and subpuna regions in northern Peruvian Andes (Gray and Cannatella 1985, IUCN 2018) in areas neighboring Celendín, Abra Comulica, San Miguel de Pallaques, and in the Province of Hualgayoc, which are all located in the Department of Cajamarca. They can be found in freshwater or inland wetlands habitats belonging to terrestrial or inland freshwater systems. Their elevational range is 2,600 - 4,300 meters (IUCN 2018). Life History, Abundance, Activity, and Special Behaviors The neurotoxin tetrodotoxin has been found in Atelopus peruensis (Mebs et al. 1995). Atelopus peruensis breeds in streams. Larvae cling to the undersides of rocks in fast-moving streams that are about 30 cm deep (IUCN 2018). Trends and Threats Atelopus peruensis is considered “Critically Endangered” because this species is declining, with an estimated 0 - 49 mature individuals left. A subpopulation of A. peruensis in Cajamarca died from water contamination resulting from gold mining. There is speculation that Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis caused A. peruensis to disappear from its entire range during the mid to late 1990s because other species known to be vulnerable to the disease and living in steams in montane cloud forest have also disappeared. Atelopus peruensis has also been collected for the pet trade in the past. Surveys are necessary to determine the current status of the species because there have been no sightings reported since 1998 (IUCN 2018). Relation to Humans Previously, A. peruensis was gathered for the pet trade but this has since ended (IUCN 2018). Possible reasons for amphibian decline Mining Comments The species authority is: Gray, P., Cannatella, D. C. (1985). “A New Species of Atelopus (Anura, Bufonidae) from the Andes of Northern Peru.” American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists 1985 (4): 910-917. Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood analyses were done in 2010 on mitochondrial fragments of 16S, tRNA-Leu, ND1, and tRNA-Ile mtDNA. Both analyses found that A. peruensis and A. longirostris belonging to the same clade and sister to the clade consisting of the A. bomolochos complex, a southeastern Atelopus clade, and the A. ignescens complex, excluding a undescribed species nominally called A. carchi. The A. bomolochos complex contains A. bomolochos, A. onorei, A. nanay, and A. exiguus. The southeastern clade includes A. podocarpus, A. halihelos, and two undescribed species that were nominally called A. condor and A. sangay from the Zamora Chinchipe and Morona Santiago states of Ecuador, respectively. The A. ignescens complex is composed of A. ignescens and an undescribed species nominally calledA. chimborazo (Guayasamin et al. 2010). Bayesian Inference and Maximum Likelihood analyses were also done on the 12S and 16S rNA mtDNA sequences in 2020. The analyses were consistent with Guayasamin et al. (2010) in that it found that Atelopus peruensis is sister to the clade that contains A. longirostris, A. spurrelli, A. chiriquiensis, A. zeteki, and A. varius (Herrera-Alva et al. 2020). The species epithet “peruensis” is a reference to Peru, the country of origin of Atelopus peruensis (Gray et al. 1985). The Andean cordilleras are fragmented by habitats with dry, low elevation interior bases in the Huancabamba Depression in northern Peru and southern Ecuador. This habitat change has acted as an obstacle to distribution along the Andes for high elevation species. These obstacles may have been lessened during glacial episodes because of paleoclimatic factors, which allowed some high elevation Andean species to travel latitudinally along the length of the larger cordilleras (Gray and Cannatella 1985).

References

Gray, P., Cannatella, D. C. (1985). “A New Species of Atelopus (Anura, Bufonidae) from the Andes of Northern Perú.” American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists 1985 (4): 910-917. Guayasamin, J. M., Bonaccorso, E., Duellman, W. E., and Coloma, L. A. (2010). ''Genetic differentiation in the nearly extinct harlequin frogs (Bufonidae: Atelopus), with emphasis on the Andean Atelopus ignescens and A. bomolochos species complexes.'' Zootaxa , 2574, 55-68. Herrera-Alva, V., Díaz, V., Castillo, E., Rodolfo, C., Catenazzi, A. (2020). “A new species of Atelopus (Anura: Bufonidae) from southern Peru.” Zootaxa, 4853 (3): 404-420. IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group. 2018. “Atelopus peruensis”. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T54539A89196220. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T54539A89196220.en. Downloaded on 05 November 2020. Lehr, E., Lotters, S., Lundberg, M. (2008). “A New Species of Atelopus (Anura: Bufonidae) from the Cordillera Oriental of Central Peru.” Herpetologica, 64 (3): 368-378. Venegas, P. J., Barrio, J. (2005). “A new species of harlequin frog (Anura: Bufonidae: Atelopus) from the northern Cordillera Central, Peru.” Asociación Herpetológica Española, 19: 103-112. Originally submitted by: Kira Wiesinger (first posted 2020-11-19) Edited by: Ann T. Chang (2022-08-02) Species Account Citation: AmphibiaWeb 2022 Atelopus peruensis: Peru Stubfoot Toad <https://amphibiaweb.org/species/72> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed Apr 23, 2025.

Feedback or comments about this page.

Citation: AmphibiaWeb. 2025. <https://amphibiaweb.org> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed 23 Apr 2025. AmphibiaWeb's policy on data use. |

Map of Life

Map of Life