|

Description

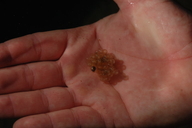

Alytes obstetricans is a small, stocky frog with a relatively large and flat head. Adults have a snout-vent length of about 39 - 55 mm. The eyes are large and have a vertical slit-shaped pupil. The skin has small warts. The parotid glands are small, and the tympanum is mostly visible. Other large gland complexes are present on the underarms and the ankles. The hands have three palmar tubercles, with long, slender digits, and the relative finger lengths of I < II = IV < III (Noellert and Noellert 1992; Salvador 1996).

Alytes dickhellini and A. muletensis do not have the orange and red dorsal dots or the marked dorsal warts that A. obstetricans possesses. Alytes cisternasii can be differentiated based on their only having two metacarpal tubercles, while other species in the genus, including A. obstetricans, have three. Other than these differences, the species in this genus tend to be quite similar, especially in the case of A. obstetricans and A. almogavarii (Arntzen and García-París 1995).

In life, the dorsal coloration is grayish brown and has varying dots from small black or brown dots to olive or green spots. The underside is a dirty white, and the throat and the chest are often spotted with gray (Noellert and Noellert 1992, Salvador 1996). There are characteristic orange or red dorsal dots as well (Arntzen and García-París 1995). The iris is a golden color (Salvador 1996).

The males are somewhat smaller than the females (Bosch and Marquez 1996). As of 2023, there are three recognized subspecies: A. o. obstetricans, A. o. pertinax, and A. o. boscai, and an additional unnamed subspecies (Ambu et al. 2023). The subspecies, A. o. pertinax, has a more elongated head and more uniform color patterns than A. o. boscai (García-París and Martínez-Solano 2001). Distribution and Habitat

Country distribution from AmphibiaWeb's database: Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland. Introduced: United Kingdom.

This species occurs in eight European countries: Portugal, Spain, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, and Switzerland. Alytes o. obstetricans occurs north of the Pyrenees and A. o. boscai occurs south of the Ebro river. The species is present practically throughout France, with the exception of the higher part of the Alps. The northernmost population is found south of Hannover, in lower Saxony, and the easternmost population is found in Northern and Central Germany (hilly regions of Thüringen and Harz). In Southern Germany the species only occurs in Baden-Württemberg in the region of the Black Forest. Alytes obstetricans prefers to live in mountainous and hilly regions (Gasc 1997).

In the Iberian Peninsula, A. obstetricans occurs from the sea shore (e.g. in Asturias and Basque Country) up to 1960 m in Portugal, and 2400 m in the Pyrenees. In the Alps, populations can be found up to 1670 m in the Bernese Oberland. In Central Europe, most populations live at altitudes between 200 and 700 m, rarely below 200 m (Gasc 1997). Life History, Abundance, Activity, and Special Behaviors

Mating season varies throughout the range. In Westfalen, Germany, one can find males carrying eggs between the end of March and the beginning of August. Around the city of La Coruña, Spain, males with clutches of eggs were observed from mid-February until August. In mountain populations, most males carry eggs well into August (Noellert and Noellert 1992).

Although males call mainly at night, they are known to call from their hiding places during the daytime. The call is high-pitched with about one call every 1 - 3 sec, usually higher and shorter than the genus Bombina. The female seeks out the male and presents herself to him, although the female has also been observed calling back in an alternating song in the mountainous regions of Germany (Noellert and Noellert 1992). The male grabs the female in the lumbar region and stimulates the female’s cloacal region by scratching it with his toes. After about 35 minutes, the male suddenly constricts the female's flanks. She extends her hind legs and ejects an egg mass. The male then releases his lumbar grip, takes an axillary hold and inseminates the eggs with a quantity of liquid sperm mass (Schleich 1996).

These frogs are well known for their male parental care behavior. Approximately 10 - 15 minutes after fertilizing the eggs, the male distends the egg mass with his hind legs, piles them alternately to his body and extends them again until the strings of eggs are wound around his ankles. The males attach the egg masses to their body and carry them until the eggs hatch (Schleich 1996). Males keep the egg mass moist by microhabitat choice, or by taking short baths. Larvae hatch after 3 to 6 weeks. The males seek out small water bodies to discard the egg strings with the hatching larvae (Engelmann et al 1985).

The females can produce up to four clutches of eggs per breeding season. A male can copulate anew and carry up to three clutches around his legs with a total of 150 eggs or more (Schleich 1996).

Alytes obstetricans prefers permanent waters, because larvae often over winter in water. The land habitat is just as important as the breeding sites: slopes, walls, embankments with many small stones, stone slabs or sand, normally with sparse vegetation are preferred. Larger colonies are observed in gravel or clay pits. Often the exposition is south, southwest or southeast and well exposed to the sun. The microclimate in the hiding places must be warm and humid (Gasc 1997; Noellert and Noellert 1992). Larva

Once hatched, the larvae are about 15 mm and metamorphose the next year, when they have reached a maximum length of 5 to 8 cm (Engelmann et al 1985).

The A. o. pertinax larvae have a color pattern more similar to Alytes dickhilleni than to A. o. boscai (García-París and Martínez-Solano 2001). Trends and Threats

The main threat to this species is the chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, otherwise known as Bd, which the species is susceptible to. Populations along the northern border, e.g., in Limburg, eastern Germany, in the Black Forest and western and central parts of the Swiss range, have disappeared for no obvious reason, but the disappearance is presumed to be disease-related. Additionally, in 1997, 1998, and 1999, mass die-offs of post-metamorphic A. obstetricans occurred in Spain, and dead frogs were found to have chytrid infections (Bosch et al. 2001). As a result there has been massive population decline, although there seems to be some slight recovery in these areas (IUCN 2022).

Populations of this species, especially on the northern border of its distribution, are threatened by disturbance from the release of fish in their breeding waters, which affects the larva (Noellert and Noellert 1992). Habitat loss is also a factor in the decline of this species; in addition to outright habitat destruction, changes affecting the microclimatic conditions (e.g., drainage) have had a negative impact on A. obstetricans (Gasc 1997). Possible reasons for amphibian decline General habitat alteration and loss

Drainage of habitat

Predators (natural or introduced)

Disease

Comments

Through a 2023 Bayesian analysis using previous samples from Maia-Carvalho et al. (2014) as well as new samples, the origins of some subspecies of A. obstetricans have been identified. In total, there are four subspecies: A. o. pertinax, A. o. obstetricans, A. o. boscai, and an unnamed taxon. Alytes obstetricans pertinax is the result of a hybridization event between Alytes almogavarii almogavarii and A. o. obstetricans. The mitochondrial sequences of A. o. boscai is more similar to A. o. obstetricans, indicating past hybridization between the two subspecies. In this same analysis, the species was shown to be sister to A. almogavarii, the two of which form a clade that is sister to the rest of the genus (Ambu et al. 2023).

This species was featured as News of the Week on 23 May 2022:

Habitat loss or modification is the biggest threat to amphibians, which includes the introduction of non-native plants. Eucalyptus globulus trees have been introduced globally from its native Australia, and its negative effects on native species, including adult amphibians, have been documented. What about other stages? Iglesias-Carrasco et al. (2022) investigated with experiments on the effects of eucalypt leachates on tadpole behavior, morphology, growth, and immune response. Rana temporaria, Alytes obstetricans, and Pelophylax perezi tadpoles were raised in mesocosms with either native oak or exotic eucalypt leachates then exposed to predator cues. The authors found that while anti-predator responses were not significantly affected, tadpoles raised in eucalypt leachates were smaller and had weaker immune responses. Furthermore, the morphology of P. perezi tadpoles in eucalypt treatments were similar to the stress morphology of other species, which may affect the tadpoles’ ability to escape predators and jump in later development. Although species varied in responses, these results indicate that the poor nutrient content and high toxicity of Eucalyptus have strong impacts at critical early stages of frog development. Further studies are needed to fully understand the long-term fitness consequences of Eucalyptus monocultures. (Written by Ann Chang) References

Ambu, J., Martínez-Solano, Í., Suchan, T., Hernandez, A., Wielstra, B., Crochet, P., and Dufresnes, C. (2023). Genomic phylogeography illuminates deep cyto-nuclear discordances in midwife toads (Alytes). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 183, 107783.

[link]

Arntzen, J. and García-París, M. (1996). Morphological and allozyme studies of midwife toads (genus Alytes), including the description of two new taxa from Spain. Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde. 65(1), 5-34.

[link]

Bosch, J. and Marquez, R. (1996). Discriminant functions for the sex identification in two midwife toads (Alytes obstetricans and A. cisternasii). Herpetological Journal, 6, 105-109.

Bosch, J., Martinez-Solano, I., and García-París, M. (2001). Evidence of a chytrid fungus infection involved in the decline of the common midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans) in protected areas of central Spain. Biological Conservation, 97(3), 331-337.

Engelmann, W.-E., Guenter, R., and Obst, F. J. (1985). Lurche und Kriechtiere Europas. Neumann Verlag, Leipzig.

Gasc, J.-P. (1997). Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles in Europe. Societas Europaea Herpetologica, Bonn, Germany.

IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group. (2022). Alytes obstetricans. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T178591974A89699462. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T178591974A89699462.en. Accessed on 12 July 2023.

Nöllert, A. and Nöllert, C. (1992). Die Amphibien Europas. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH and Company, Stuttgart.

Salvador, A. (1996). Amphibians of Northwest Africa. Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service, 109.

Schleich, H. H., Kastle, W., and Kabisch, K. (1996). Amphibians and Reptiles of North Africa. Koeltz Scientific Publishers, Koenigstein.

Originally submitted by: Arie van der Meijden (first posted 1999-09-22)

Edited by: Vance T. Vredenburg, Kellie Whittaker, Michelle S. Koo, Ann T. Chang (2023-08-09)Species Account Citation: AmphibiaWeb 2023 Alytes obstetricans: Midwife Toad <https://amphibiaweb.org/species/1522> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed Jul 26, 2024.

Feedback or comments about this page.

Citation: AmphibiaWeb. 2024. <https://amphibiaweb.org> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed 26 Jul 2024.

AmphibiaWeb's policy on data use.

|

Map of Life

Map of Life