|

Description

A medium-sized toad. Distinguishing characters include a white or cream dorsal stripe and lack of cranial crest. This species has two known subspecies, Anaxyrus boreas boreas and A. b. halophilus.

A. b. boreas is dusky gray or greenish above with warts set in dark blotches, often mixed with a bit of rusty color. Males are usually less blotched with smoother skin and are smaller than females (Stebbins 1985).

Distribution and Habitat

Country distribution from AmphibiaWeb's database: Canada, Mexico, United States U.S. state distribution from AmphibiaWeb's database: Alaska, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming Canadian province distribution from AmphibiaWeb's database: Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon

Populations of A. b. halophilus are found in California, western Nevada, and northern Baja California. Populations of A. b. boreas are found in southern Alaska, British Columbia, Alberta, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, northern California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. This toad frequents a wide variety of habitats such as desert streams, grasslands, woodlands, and mountain meadows, and can be found in or near a variety of water bodies (Stebbins 1985).

Life History, Abundance, Activity, and Special Behaviors

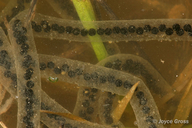

This species is an explosive breeder. Females deposit thousands of eggs in long strings, usually in shallow ponds. These toads are nocturnal at low elevations and diurnal at higher elevations. During the winter, A. boreas buries itself

in loose soil or uses the burrow of a small mammal (Stebbins 1985).

This species tends to walk rather than hop. Both males and females lack an advertisement call (Duellman and Trueb 1986) although they are known to have a release call (Brown and Littlejohn 1971).

Trends and Threats

UV-B radiation has been shown to cause reduced hatching success in

Oregon (Blaustein et al. 1994), but not in Colorado, although

more investigation is needed (Corn 1998).

Synergistic effects between UV-B and an alga, Saprolegnia ferax , have

also been shown to cause reduced hatching success in

Oregon (Kiesecker and Blaustein 1995).

Vertucci and Corn (1993) found that acid precipitation may not be

a major cause of the decline of A. b. boreas in Colorado, but more

investigation of this problem is needed (Stebbins and Cohen 1995).

A. boreas tends to lay its eggs in communal masses, and such communal egg masses have

been shown to be highly susceptible to infection with S. ferax

(Kiesecker and Blaustein 1997).

In the southern Rocky Mountains, translocation was tried for A. b. boreas. The translocation projects failed; A. b. boreas has been declining in that area for unknown reasons, for some time (Trenham 2001).

Possible reasons for amphibian decline Habitat modification from deforestation, or logging related activities

Prolonged drought

Habitat fragmentation

Disease

Weakened immune capacity

Climate change, increased UVB or increased sensitivity to it, etc.

Comments

It has been known to occasionally hybridize with the Red-spotted Toad (Anaxyrus punctatus) and the Canadian toad (Anaxyrus hemiophrys) (Stebbins 1985).

This species was featured as News of the Week on 21 February 2022:

How will increasing temperatures from the climate crisis impact amphibian aging and mortality? Despite its relevance to conservation, little data exists on the relationship between temperature and senescence in free-living animals. Cayuela et al. (2021) studied pairs of frogs from two families divided by 100 million years of evolutionary history to answer this: Rana luteiventris and R. temporaria (Ranidae) and Anaxyrus boreas and Bufo bufo (Bufonidae). The North American toads (Bufonidae) represented sampling along a climatic gradient, whereas the ranid frogs represented sampling from climatically contrasted sites. They found that actuarial senescence rates— i.e., the rate at which mortality increases with age— increased with the mean annual temperature experienced in all species. In all species but Anaxyrus boreas, increasing temperatures corresponded to decreasing lifespans. These relationships are presumably attributed to amphibians' increasing pace of life with increasing temperatures; they are active for longer periods, have a higher metabolism, lower mitochondrial efficiency, and accumulate oxidative damage more rapidly. The impacts of increasing temperature on these frogs might be exacerbated by increasing evaporative water loss and influenced by genes involved in adapting amphibians to warmer conditions. In the ranids studied, the authors found increasing temperatures flipped sex differences in senescence rate in R. luteiventris but not R. temporaria. These results paint a grim picture for amphibians as global temperatures increase. Amphibian aging is expected to accelerate, with potential skewing sex ratios in some species. (Written by Emma Steigerwald)

See subspecies accounts at www.californiaherps.com: B. b. boreas and B. b. halophilus .

References

Blaustein, A. R., Hoffman, P. D., Hokit, D. G., Kiesecker, J. M., Walls, S. C., and Hays, J. B. (1994). "UV repair and resistance to solar UV-B in amphibian eggs: A link to population declines?" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 91(5), 1791-1795.

Brown, L. E. and Littlejohn, M. J. (1971). ''Male release call in the Bufo americanus group.'' Evolution in the Genus Bufo. W. F. Blair, eds., University of Texas Press, Austin, 310-323.

Corn, P. S. (1998). "Effects of ultraviolet radiation on boreal toads in Colorado." Ecological Applications, 8, 18-26.

Duellman, W. E., and Trueb, L. (1986). Biology of Amphibians. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Kiesecker, J. M., and Blaustein, A. R. (1995). "Synergism between UV-B radiation and a pathogen magnifies amphibian embryo mortality in nature." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 92(24), 11049-11052.

Kiesecker, J. M., and Blaustein, A. R. (1997). "Influences of egg laying behavior on pathogenic infection of amphibian eggs." Conservation Biology, 11(1), 214-220.

Stebbins, R. C. (1985). A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Stebbins, R. C., and Cohen, N. W. (1995). A Natural History of Amphibians. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Trenham, P. C., and Marsh, D. M. (2001). ''Amphibian translocation programs: reply to Seigel and Dodd.'' Conservation Biology, 16(2), 555-556.

Vertucci, F. A., and Corn, P. S. (1996). "Evaluation of episodic acidification and amphibian declines in the Rocky Mountains." Ecological Applications, 6(2), 449-457.

Originally submitted by: Erica Garcia (first posted 1999-04-07)

Edited by: Vance T. Vredenburg, Joyce Gross, Kellie Whitaker, Michelle S. Koo (2022-02-20)Species Account Citation: AmphibiaWeb 2022 Anaxyrus boreas: Western Toad <https://amphibiaweb.org/species/122> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed Nov 22, 2024.

Feedback or comments about this page.

Citation: AmphibiaWeb. 2024. <https://amphibiaweb.org> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed 22 Nov 2024.

AmphibiaWeb's policy on data use.

|