|

Description

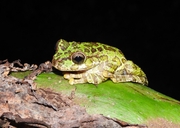

Charadrahyla nephila is slender-bodied frog with adult males having a snout vent length range of 52.9 – 61.9 mm and females having a range of 59.6 - 80.7 mm. The head is similar in width and length and has a flat top. In both the profile and dorsal views, the snout is rounded and lacks a rostral keel. The nostrils are oval, slightly protuberant, and directed laterally. The canthus rostralis is angular and distinct. The internarial and loreal region are concave. The eye diameter is narrower than the interorbital region. The distinct, round tympanum is about half the diameter of the eye wide. The distance from the eye to the tympanum is about 3/4ths of the width of the tympanum. On the anterior edge, the tympanic annulus is distinctly raised, but indistinct on posterior and ventral edge and obscured on the dorsal edge by the supratympanic fold. The supratympanic fold is distinct, thick, and connects the posterior margin of the eye to the forearm where it becomes indistinct (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

The skin on the dorsal surfaces is smooth while on the ventrum it is granular. The body does not have any axillary membranes or thoracic folds. The cloaca is at the level of the mid-thigh, directed postroventrally, and has a short sheath (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

There is a dermal fold on the wrists and large ulnar tubercles that merge to form a fleshy ulnar ridge. There is a large, rounded, bifid palmer tubercle and a distinct, elliptical prepollical tubercle that is 3.5 times larger than the subarticular tubercles. The granular nupitial excrescences form a small triangular patch at the base of finger I on the dorsal surface. The long, slender fingers have broad lateral fringes and end in large ovoid discs that are relatively the same size as the tympanum, except finger I, which is about a quarter smaller than the rest. The fingers have relative lengths of I < II < IV < III, small, rounded subarticular tubercles that are a fourth of the width of the discs, and even smaller, indistinct, round supernumerary tubercles. The hands have thin webbing with a formula of I2⅔ - 2¾ II 1¾ - 3III2¼ - 2IV (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

When the legs are adpressed at right angles to the body, the hindlimbs overlap. When adpressed along the body, the tibiotarsal articulation reaches the snout. The tibia is longer than the foot. A tarsal fold is present as is a distinct, large, ovoid inner metatarsal tubercle. There is no outer metatarsal tubercle. The long, slender toes have a broad lateral fringe and end with ovoid terminal discs that are slightly smaller than the fingers. The subarticular tubercles are distinct, large, elevated, round and about half the size of the terminal discs of the same toe. The supernumerary tubercles are also distinct and rounded, but arranged along the axis of the phalange in a row. The toes have thin webbing with a formula of I½ - 2II1 – 2III1¼ - 2IV2 – 1V (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

Tadpoles, at stage 25, have body length of around 9.4 mm and a total length of around 28 mm. At stage 42, body lengths range from 20.0 - 23.0 mm. The body is small, and about as high as it is wide. The snout is slightly rounded from an above and acutely rounded from a lateral view. The nostrils sit equidistant from the eyes to the snout and are directed anterolaterally. The eyes are about a one-sixth of the body height and positioned and directed dorsolaterally. The mouth is positioned anteroventral, is directed ventrally, and is not as wide as the body. Two to three rows of papillae completely surround the mouth with additional, scattered, lateral papillae. There are two rows of upper teeth, and four lower rows. The upper tooth rows are equal in length and longer than the lower rows. The first three lower tooth rows are equal in length and the fourth is shorter. The massive jaw sheaths have large serrations. The spiracle is on the sinistral side of the body and has a posterodorsal opening. The anal tube is on the dextral side of the body. Several rows of lateral lines are along the midline extending from the snout across the body. The tail is robust with heavy musculature that extends almost to the rounded tip. The fins are shallow and do not extend onto the body. At the midline of the tail the fins are shorter than the caudal musculature (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

Male C. nephila are distinguishable from other similar species, such as C. taeniopus, due to the presence of vocal slits in male C. nephila that sit under the lower jaw on both sides laterally. They are distinguishable from C. alipotens due to the shape of the snout not tapering to a point in both sexes of C. nephila. The texture of the skin on the back of the frog is smooth, unlike the more granular skin of other members in the same family, such as C. chaneque (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

In life, males and females are sexually dimorphic with regards to color. Males have a gray-brown dorsal background color while females reddish-brown. Both sexes have pigmented patches that are green with brown outlines, however some males may have uniformly dark brown spots. In males, the leg bars on the thighs and shanks are brown, while in females they are suffused with green. The flanks of males is cream, pale tan, or pale green with dark brown to black spots while in females the spots are medium brown, suffused with green. In both sexes, the region below the supratympanic fold and the loreal region are also fussed with green. The ventral coloration is purplish, with the gular and chest being darker than the belly. The chest and the throat area typically have pale flecking. The iris color ranges from pale copper to bronze with fine black reticulations. When in preservative, color is dulled, and the frogs do not appear sexually dimorphic regarding coloration. The head and body are pale brown in color, with darker brown patches. The legs have deep brown stripes circling the limbs, which is a diagnostic trait for the genus Charadrahyla. Ventral coloration is variable from light brown, dull grey, to dull cream and may or may not have white to cream flecks (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

Although there is no morphometric differences between the sexes besides adult female C. nephila being larger than adult males, there are sexual differences in coloration. The dorsal background color of females is reddish-brown while males are gray-brown to mauve. Additionally, the leg bars in females have green pigments suffused throughout while males are dark brown. Females also have brown spots suffused with green pigment on the lower flanks while in males the flanks are cream, pale tan, or pale green with dark brown to black spots. In preserved specimens, the ventral coloration and patterning is variable between individuals, ranging from uniformly brown, dull gray, to dull cream and any of these background colors may have white to cream flecks (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

Distribution and Habitat

Country distribution from AmphibiaWeb's database: Mexico

Charadrahyla nephila can be found on the Atlantic slopes of the Sierra Zongolica, Sierra de Juárez, and Sierra Mixe in Oaxaca, Mexico at elevations ranges between 680 – 2256 m. These sites are composed of inland wetlands and cloud-forests. More specifically, Adults were found at night on larger boulder or vegetation along streams (Santos-Barrera and Canseco-Marquez 2004).Life History, Abundance, Activity, and Special Behaviors

Adults were most often found at night on boulders and vegetation along streams through the mountains where breeding occurs (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

Breeding is thought to occur year round with females having 980 – 2103 ovarian eggs that have diameters of 1.76 – 2.66 mm (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

Calls originally thought to belong to C. chaneque are now known to be those of C. nephila. The calls produced by this species are composed of one note of a low frequency (Mendelson and Campbell 1999, Duellman 2001).

Larva

In life, the dorsum of the tadpole is brown, the sides yellow, and the ventrum is dark gray. There are pale green iridiophores forming streaks on the body. The caudal fins are overall transparent, but have scattered brown spots and distinct yellow xanthophores that form a yellow edge along the dorsal fin. The xanthophores are also found on the caudal musculature. The iris is yellow. When preserved, the entire body becomes brown and the caudal musculature becomes yellowish tan. The fins retain their transparency and patterning (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

Trends and Threats

Populations of C. nephila are decreasing. This is likely due to deforestation from logging. Emerging diseases, such as chytridiomycosis from Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, may also be leading to the decline (Santos-Barrera and Canseco-Marquez 2004, Frías-Alvarez et al. 2010). Possible reasons for amphibian decline General habitat alteration and loss

Habitat modification from deforestation, or logging related activities

Habitat fragmentation

Comments

At the time of the genus description, Charadrahyla, was composed of five species: C. altipotens, C. chaneque, C. nephila, C. taeniopus, and C. trux; this was determined by 56 transformation in the ribosomal genes as well as the nuclear and mitochondrial proteins. The genus Megastomatohyla is closely related to Charadrahyla (Faivovich 2005). By 2019, three more species were described, C. tecuani by Campbell et al. (2009), C. esperancensis by Canseco-Márquez et al. (2017), and C. sakbah by Jiménez-Arcos et al. (2019). Genetic analysis is needed to reveal the relationships within the genus.

When first described, C. nephilia was thought to be sister to C. chaneque, from which it was split, based on morphology, close geographic ranges, and habitat preferences. However this relationship was not molecularly tested (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

The species was first described as Hyla nephila (Mendelson and Campbell 1999).

This species was featured in News of the Week 21 October 2024:

Mexico is a great place in terms of biodiversity, and amphibians (and reptiles as well) contribute to that claim. Although it does not possess a huge quantity of species, more than 70% of the amphibian species that occur in the country are endemic to it. Lemos-Espinal and Smith (2024) analyzed the Mexican herpetofauna, amphibian and reptiles together, and found that the Transition Zone —the area where Nearctic and the Neotropical biogeographic regions converge— had the greatest species richness, housing 90.8% of the amphibian species and 71.1% of the reptile species that inhabit Mexico. Amphibian and reptile richness follow the latitudinal gradient of diversity [greater species richness towards the equator], with the highest richness in the biogeographic province of Sierra Madre del Sur, followed by the Trans-volcanic Belt and the Sierra Madre Oriental. The first two are included in the Transition Zone. They also found that geographic proximity is related to the similarity species composition –the nearer the more similar. They provide a presence-absence matrix with data for all the biogeographic provinces and an updated species list. The data will be useful for conservation of amphibians and reptiles in Mexico. (Written by Leticia Ochoa Ochoa)

References

Campbell, J. A., Blancas-Hernández, J. C., Smith, E. N. (2009). ''A new species of stream-breeding treefrog of the genus Charadrahyla (Hylidae) from the Sierra Madre del Sur of Guerrero, Mexico.'' Copeia, 2009(2), 287-295. [link]

Canseco-Márquez, L., Ramírez-González, C.G., González-Bernal, E. (2017). ''Discovery of another new species of Charadrahyla Anura, Hylidae) from the cloud forest of northern Oaxaca, México.'' Zootaxa, 4329(1), 64-72. [link]

Duellman, W. E. (2001). The Hylid Frogs of Middle America. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Ithaca, New York.

Faivovich, J., Haddad, C. F. B., Garcia, P. C. A., Frost, D. R., Campbell, J. A., Wheeler, W. C. (2005). ''Systematic review of the frog family Hylidae, with special reference to Hylinae: phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision.'' Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, (294), 1-240. [link]

Frías-Alvarez, P., Zúñiga-Vega, J.J., Flores-Villela, O. (2010). ''A general assessment of the conservation status and decline trends of Mexican amphibians.'' Biodiversity Conservation, 19, 3699-3742.

Jiménez-Arcos, V.H., Calzada-Arciniega, R.A., Alfaro-Juantorena, L.A., Vázquez-Reyes, L.D., Blair, C., Parra-Olea, G. (2019). ''A new species of Charadrahyla (Anura: Hylidae) from the cloud forest of western Oaxaca, Mexico.'' Zootaxa, 4554(2), 372-385. [link]

Mendelson, J.R., Campbell, J.A. (1999). ''The taxonomic status of populations referred to Hyla chaneque in southern Mexico, with the description of a new treefrog from Oaxaca.'' Journal of Herpetology, 33(1), 80-86. [link]

Santos-Barrera, G., Canseco-Márquez, L. (2004). “Charadrahyla nephila”. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2004: e.T55577A11321043. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2004.RLTS.T55577A11321043.en. Downloaded on 11 May 2019.

Originally submitted by: Heather Baker (first posted 2019-09-10)

Edited by: Ann T. Chang, Michelle S. Koo (2024-10-20)Species Account Citation: AmphibiaWeb 2024 Charadrahyla nephila: Oaxacan Cloud-Forest Treefrog <https://amphibiaweb.org/species/5467> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed Jan 3, 2025.

Feedback or comments about this page.

Citation: AmphibiaWeb. 2025. <https://amphibiaweb.org> University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed 3 Jan 2025.

AmphibiaWeb's policy on data use.

|

Map of Life

Map of Life